Worldheritage

History

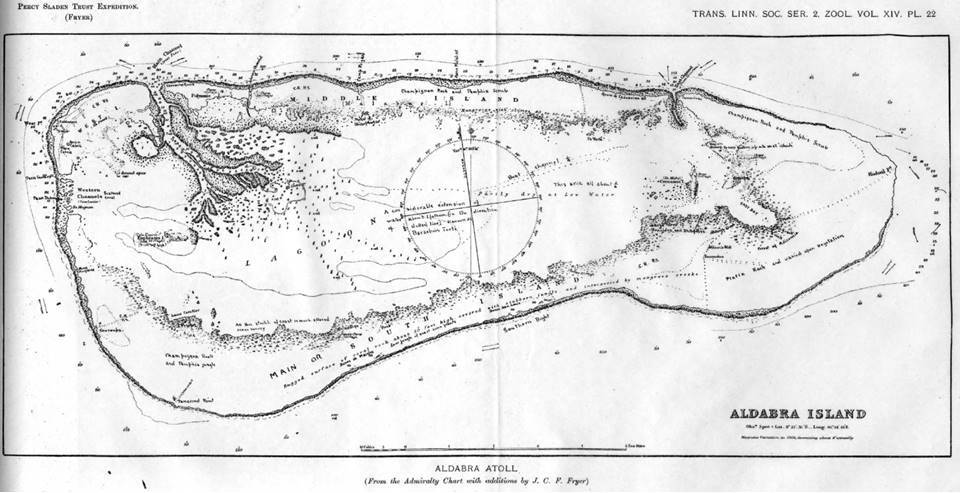

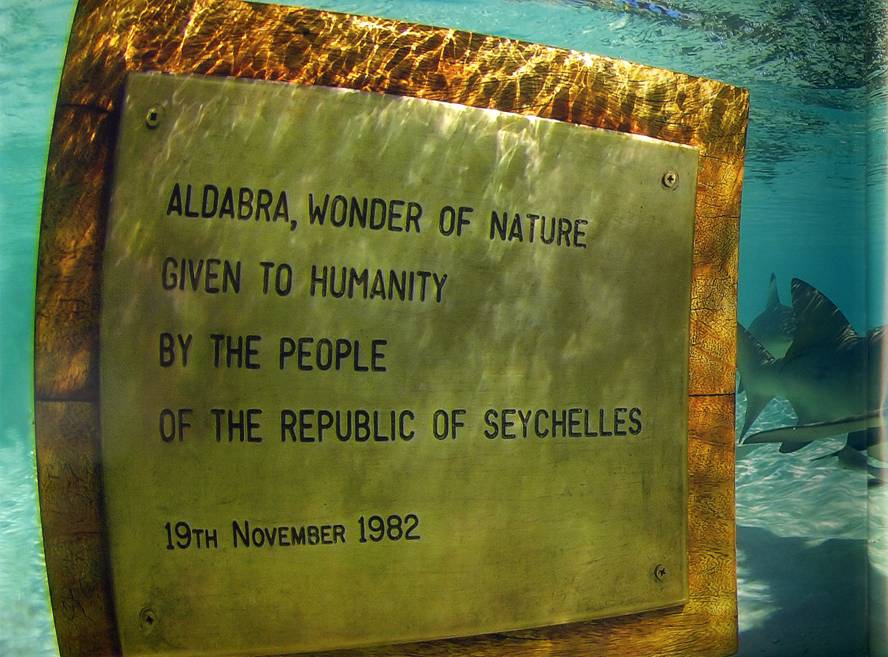

Aldabra is reported to have been first discovered by a group of Arabs during an exploratory trip in the Indian Ocean in 916 AD. The name Aldabra is reported to have come from the Arabic word ‘Al-Khadra’ which means ‘the green’, in reference to the lagoon’s green reflection on the clouds above it. There is also another suggestion that the name was derived from the star ‘Aldabaran’ which was used by early Arab sailors to chart their sailing course. In 1742, as the islands of Seychelles were seized by the French, Captain Lazard Picault was sent to Seychelles and to Aldabra to assess their potential. On Aldabra, the crew were astonished by the size of the giant tortoises and valued them as a source of meat, but they found the granitic islands more useful and Aldabra was considered “not good for anything”. Aldabra’s remote location and harsh environment deterred permanent human settlement for many years. This is not to say however, that it did not escape exploitation despite Picault’s early derogatory assessment of the atoll.

Key species & habitats

Red-footed boobies (Sula sula) spend most of their time at sea but they come ashore in their thousands to nest on Aldabra. The smallest of the booby species, the red-footed booby is named for its distinctive scarlet feet. These boobies can appear in a variety of colour morphs with juveniles usually having a brown body, but all adults have red feet and a blue bill. This gregarious species breeds in large raucous colonies on Aldabra where it nests alongside both species of frigatebird. Red-footed boobies are powerful flyers and can fly up to 150 km in search of food. They are well adapted for diving and plunge-dive to catch fish they spot from the air, often diving to 30 m to pursue their prey. When nesting at Aldabra they leave the atoll to fish and return to the breeding colony to feed their young or mate. The frigatebirds are wise to these habits and can often be seen in groups harassing boobies as they return to the colony. Constant chasing often causes the boobies to drop their catch, giving the pursuing frigatebirds a free meal!

The Aldabra banded snail (Rhachistia aldabrae), declared extinct in 2007, was re-discovered on Malabar island in August 2014. Before the discovery, the last living individual of this Aldabra endemic species was recorded in 1997. Subsequent searches yielded only shell remains. The snail’s apparent demise was linked to declining rainfall on Aldabra and was widely publicised internationally as one of the first casualties of climate change impacts.

The Aldabra banded snail has been recorded historically from the islands of Picard, Malabar, Polymnie, Esprit and Grande Terre but very little is known about its ecology. This rediscovery provides an incredible second chance to protect and study this species in the wild and ensure that it is not lost again. Climate change may not have caused the demise of this snail, but climate change impacts remain a likely threat to this species and many others globally so it will be monitored regularly on Aldabra.

Coral reefs are one of the most important but rapidly declining ecosystems in the world’s tropical oceans. On Aldabra however, the reefs remain relatively untouched from direct human impacts due to decades of protection.

The coral reefs at Aldabra are sculpted by the constant push and pull of the tides flowing in and around the atoll. The channels into the central lagoon are formed of low profile corals that are shaped by the constant force of the tidal current. The fringing reefs host a dense profusion and diversity of marine life, owing to the rich coral communities that in turn encourage abundant invertebrate and fish life. On the shallow reefs the fish diversity is outstanding, with one study recording 185 species of fish in 3 km2 of reef. This healthy marine food web has a high prevalence of apex predators, including many large snappers, groupers and sharks. As well as the complex coral reef life, the reefs are also visited by pelagic or oceanic species such as manta rays and whale sharks.

In 1998, high sea surface temperatures caused one of the largest coral bleaching events recorded in the Indian Ocean which produced a coral mortality rate of up to 95% in Seychelles. Aldabra’s reefs also suffered, however it was one of the few places where the recovery process could be monitored in the absence of human interference. A long-term marine monitoring programme has now been developed that allows for detection of changes to the marine ecosystem as a response to environmental or anthropogenic pressures, and will serve as an indicator of marine ecosystem health. Despite the absence of direct human impacts on Aldabra, indirect threats such as sea level rise, ocean acidification and climate change all threaten the atoll’s magnificent reefs. Fortunately the healthy coral ecosystem at Aldabra means that the reefs are more resilient than those facing more localised threats.

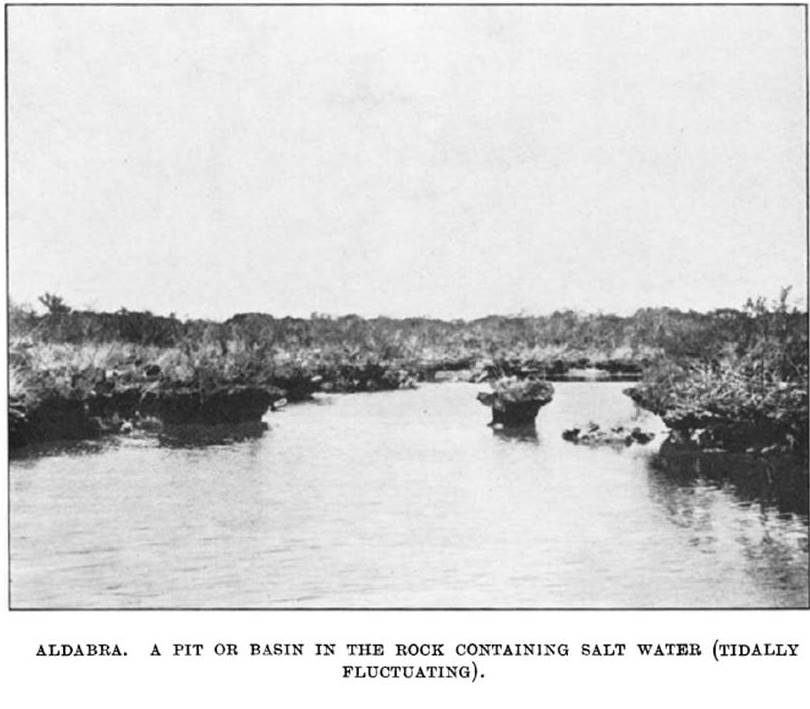

Covering 25,100 ha (over half the area of the whole atoll) the wetland ecosystem of Aldabra was listed as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention in 2009. These wetlands at Aldabra include the extensive shallow lagoon inside the atoll, which is carpeted with lush seagrass beds and patchy coral reefs, the intertidal mud flats, the coral reefs outside the lagoon (see next section), freshwater pools, beaches, and 2000 ha of mangrove stands. These wetlands support several endangered species including the increasing number of nesting turtles at the atoll, dugongs and many other bird, fish and invertebrate species. Seven species of mangrove are found on Aldabra. They form a dark, green forest that is as much as 1.5 km wide and over 10m high in some places. Above water this forest provides crucial nesting habitat for two species of frigatebird and the red-footed booby. Underwater, the trees’ complex root system forms an important breeding ground for many species of fish, including sharks and a safe area for juvenile turtles. Compared to the early 20th century, when some components of Aldabra’s wetlands were exploited, most notably for mangrove wood, the wetland ecosystems of Aldabra now face different threats. Sea level rise due to climate change, ocean acidification, global warming and invasive alien species all pose threats to this complex set of ecosystems. Long-term monitoring of these habitats is therefore essential to assess trends and changes.

The unmistakeable symbol of Aldabra Atoll, the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea) is a huge prehistoric-looking reptile which is one of the last two living representatives of giant tortoises in the world.

Giant tortoises were once widespread on islands across the world, but hunting by man exterminated all species in the Indian Ocean apart from Aldabra’s. Even Aldabra’s tortoises were exploited for many years and dangerously reduced in numbers but, due to the protection afforded to Aldabra since the 1960s and, under SIF’s protection since 1979, the tortoise population has recovered to and is by far the largest population of giant tortoises in the world. The only other living species of giant tortoise in the world, the famous Galápagos giant tortoise, exists in numbers that are dwarfed by the lesser known Aldabra population.

The presence and sheer abundance of giant tortoises makes Aldabra’s ecology unique. It is the only place in the world where a giant herbivorous reptile is the most dominant animal. Its dominance drives Aldabra’s terrestrial ecosystem; for example, one entire habitat type, ‘tortoise turf’ is not only named for, but depends on the presence of the tortoises. The survival of giant tortoises on Aldabra provides a fascinating insight into how these ecosystems evolved and functioned. Because of this, giant tortoises and their interactions form an integral part of SIF’s research and monitoring work on the atoll.

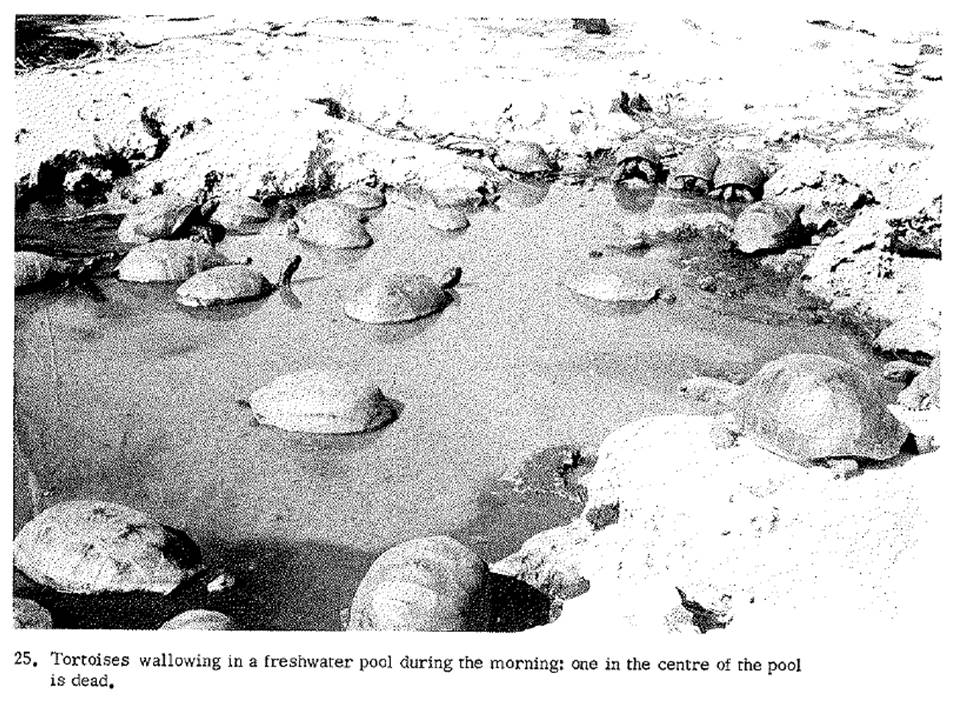

The giant tortoises are perfectly adapted for surviving in Aldabra’s harsh terrain and climate. They can live for weeks without food and water which enables them to survive Aldabra’s aridity and extended dry season. They drink large amounts of water when it is available which they store in their bladders for long periods of time. Incredibly, they have an adaptation that allows them to drink through their nostrils. Combined with the shape of their snout, this allows them to drink water from small and shallow puddles that they otherwise could not drink from. The giant tortoises can also swim, which can come in handy when caught by the rapidly moving tide. Indeed they are so successful that they are one of the world’s longest-living animals, living to more than 100 years in the wild and over 200 years in captivity.

The Aldabra rail (Dryolimnas cuvieri aldabranus) or ‘Tyomityo’ (in Creole) is the last surviving flightless bird in the Western Indian Ocean. The survival and management of this iconic bird on Aldabra is a conservation success story for the atoll. The curious and charismatic rail was wiped out on two of Aldabra’s four main islands (Grande Terre and Picard) by introduced feral cats and as a result was restricted to only three islands of the atoll (Malabar, Polymnie and the tiny lagoon island of Ile aux Cedres).

After cats died out on Picard, 18 Aldabra rails were successfully re-introduced to the island from Malabar in 1999. This re-introduction was a great success and in 2012 the Picard population had reached almost 3000 birds, putting the estimated total population at 10,000 breeding pairs of rails across Aldabra (Sur et al, 2013b). The future for the rail now looks more secure, although its small range and vulnerability to predators, particularly cats, means that it will continue to be monitored closely and eradication of cats from Grande Terre is under consideration.

An inquisitive and lively bird, rails will often investigate any strange object as potential food. They have a varied diet including small reptiles and invertebrates that they pluck from the leaf litter. They can often be seen following giant tortoises to feed on anything that has been disturbed or dislodged by the tortoise’s movement. As well as feeding in the leaf litter, rails commonly eat small molluscs and crabs.

Flightless rail species used to live on several other islands in the Western Indian Ocean, including Assumption, Mauritius and Rodrigues. All except the Aldabra rail and the Madagascar white-throated rail (of which the Aldabra rail is considered a sub-species) are now extinct leaving the Aldabra rail as the only remaining flightless species. Genetic research is underway to determine whether the Aldabra rail should be considered a distinct species to its volant Madagascan relative.

Aldabra has the second largest population of nesting green turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the Western Indian Ocean. Lush sea grass beds, diverse coral reefs and undisturbed beaches provide an ideal habitat for these graceful long-lived reptiles. Green turtles are listed by IUCN as globally endangered due to severe declines in their numbers caused by hunting, fishing by-catch and coastal habitat modification. Prior to 1968, when Aldabra was established as a nature reserve, Aldabra’s green turtles also suffered intense exploitation for their meat. Following several decades of protection under SIF however, and the addition of the Turtle Protection Act in 1994 to the Wild Animals and Birds Protection Act (1961), this turtle population has soared. Between 1968 and 2008 there was an astonishing 500–800% increase in the number of nesting green turtles on Aldabra, with around 3100–5225 female turtles recorded as nesting annually in 2008 (Mortimer et al, 2011). This number has continued to increase and if current trends are sustained it is likely that Aldabra will become the most important nesting site in the region for this endangered species. This has been an incredible conservation success and clearly demonstrates the importance of protection for these ocean wanderers. To learn more about where these long-distance travellers go, when not at Aldabra, research has been conducted into their movements using satellite transmitters. Eight of Aldabra’s nesting green turtles had transmitters attached, which allowed us to track their movements for a few months. The tagged turtles migrated away from Aldabra into the territorial waters of at least six countries and used locations across the Western Indian Ocean to feed and rest while away from Aldabra. This research found no set pattern of migratory route or fixed foraging location for the small number of turtles tagged. The research has underlined the need for transboundary protection measures for marine turtles and the importance of international instruments such as the Convention on Migratory Species, to which Seychelles is a party, and the Indian Ocean South East Asia (IOSEA) Marine Turtle Memorandum of Understanding. Aldabra was accepted into the Network of Sites of Importance for Marine Turtles in the Indian Ocean – South East Asia Region.

Once common throughout Seychelles’ waters, the gentle Dugong (Dugong dugon) was another victim of early settlers who hunted them for their meat. Now, the only remaining population of dugongs in Seychelles is found at Aldabra. Aldabra’s large, shallow lagoon of 200 km2 and extensive seagrass beds provide ideal habitat for these large marine mammals. Sightings of one or two animals were recorded as far back as 1970 but it was only recently that a more comprehensive survey of the dugong population was attempted by SIF. The partial aerial survey of the lagoon recorded a minimum of 14 dugongs in the area covered, which is by far the largest number counted to date and suggests that the population may be larger. This exciting discovery has instigated further questions; are these dugongs resident or are they travelling from the East African coast? Further aerial surveys and research into the dugongs’ movements are needed to help answer these questions but so far the high costs of this research have prevented it from going ahead. The dugong and its sirenian relatives (the sea cows – including manatees) are the only marine mammals that feed exclusively on plants. They have a low metabolic rate and generally move relatively slowly at about 10 kilometres per hour. As a seagrass specialist, dugongs inhabit mainly shallow tropical waters throughout the Indo-Pacific. Unfortunately dugongs’ preference for shallow coastal waters and their slow-movements have made them easy targets and led to their persecution worldwide for meat and oil. Dugongs are also vulnerable to changes to seagrass ecosystems, upon which they depend, and fishing nets and boat strikes have been a major cause of population decline. Their low reproductive rate, long period between offspring and high investment in each offspring means that dugongs are slow to recover from declines in their population.

Aldabra hosts the largest frigatebird breeding colony in the Indian Ocean and the second largest colony in the world, with both the greater frigatebird (Fregata minor) and lesser frigatebird (F. ariel) nesting in the same mangrove colonies surrounding the vast lagoon. Seabird populations are an indicator of the health of the oceans, and Aldabra’s numerous frigatebirds, along with thriving populations of several other seabird species, are one indication that the marine ecosystem is rich and healthy.

There are four main nesting frigatebird colonies on Aldabra in the mangroves of several islands. In 2011 a colony finally re-established on Picard Island after an absence of over a century. Both species of frigatebird nest in mangroves alongside large colonies of red-footed boobies. Recent research has shown large annual fluctuations in the number of nesting frigatebirds but the trend indicates that the population has increased overall by at least 10% since 2000 (Sur et al, 2013a). The cause of these fluctuations is unknown but is thought to be related to the varying annual availability of their food, including squid and flying fish. Annual monitoring of these colonies is providing more data with which to understand these fluctuations and possible causes. Frigatebirds are highly sensitive to disturbance so extreme care is always taken when viewing the colonies. One outcome of this research was that SIF further revised the strict frigatebird colony visiting guidelines to ensure that that the Aldabra frigatebird population is not disturbed.

Frigatebirds have the largest wing area to body mass ratio of any bird and this allows them to make spectacular flight manoeuvres. They use their manoeuvring skills to great effect when harassing other seabirds in flight until they drop their catch, which is then quickly caught by the pursuing frigatebirds. This type of feeding (‘kleptoparasitism’) is also the origin of their name. Although frigatebirds spend a great amount of time soaring over the ocean they do not have waterproof plumage or webbed feet. This means that, unlike other seabirds, if frigatebirds get wet it is very difficult for them to fly until their plumage dries.

Although found across the tropical waters of the world, Aldabra supports the largest breeding population of red-tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon rubricauda) and white-tailed tropicbirds (P. lepturus) in Seychelles. These graceful and elegant seabirds breed on many oceanic islands. On Aldabra they breed on small islets, and some coastal areas, where there are no cats and fewer rats. Despite their aerial acrobatics and impressive ability in the air and water these birds are very vulnerable when nesting. Nesting success rates are low for both species of tropicbird on Aldabra and this is at least partly due to the high incidence of various native and introduced nest predators. Camera traps are used to monitor tropicbird nests on Aldabra and footage has shown that the Aldabra drongo is an unexpected additional nest predator of these seabirds! The movements of tropicbirds when they are not breeding at Aldabra were, until recently, shrouded in mystery. A pilot project in 2012 shed first light on their migratory movements and revealed that one of Aldabra’s tropicbirds flew to the Chagos archipelago and back to Aldabra in a period of a few months, a round journey of about 5000 km! This work, and further research into the breeding success of these striking seabirds, is planned to be followed up soon.

Common in the waters around Aldabra, the blacktip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) is a powerful swimmer and curious by nature. Known to occur in extremely shallow water, Aldabra is no exception for these sharks, with blacktips often seen in water only 30 cm deep with their dorsal fins exposed. Blacktips are seen all around the atoll, in the lagoon, mangroves and the outer coral reef areas. Encountered both singly and in small groups the sharks feed on a variety of small fish and invertebrates.

Blacktip reef sharks have a wide range, occurring in the western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and the eastern Mediterranean. Classified as Near Threatened by IUCN, globally the blacktip reef shark is under pressure from the shark fin trade and human consumption. It is also vulnerable due to its small litter sizes and long gestation period. The protected waters of Aldabra offer a safe haven for this and several other species of shark, where they form an essential part of the food web as apex predators and keep the ecosystem healthy.

The world’s largest terrestrial arthropod, coconut crabs (Birgus latro) thrive on Aldabra and are a fundamental part of its terrestrial ecosystem. Also known as ‘robber crabs’ these powerful crabs live up to their name and are capable of de-husking whole coconuts and opening the shell to feast on the flesh inside. The crabs are related to hermit crabs and use empty shells when they are young for protection. Once they develop their tough outer shell, or exoskeleton, they no longer need other shells and grow to relatively gigantic proportions, with specimens known (although not from Aldabra) of up to 1 m in diameter and over 4 kg in weight! Their huge size is thought to be approximately the upper size limit for terrestrial animals with exoskeletons in recent geological time. Aside from their unusual appearance, these crabs, along with the millions of other crabs on the atoll, provide an essential service within Aldabra’s ecosystem as they have an indiscriminate diet and will scavenge carrion, as well as consuming plant matter, rapidly removing decaying material from the environment and playing an important role in nutrient recycling on the atoll. Although a terrestrial species, as adults these crabs made their way to Aldabra as larvae carried on the ocean’s currents. All coconut crabs deposit their eggs at sea where the larvae spend many months developing before they emerge on land. Adults are primarily nocturnal and get protection from digging burrows or using natural holes and crevices for shelter during the day. These holes are also used when the crabs need to moult their exoskeleton. As darkness falls, the coconut crabs emerge creeping from their burrows in their hundreds creating a remarkable, and some think sinister scene. Breeding female coconut crabs become laden with eggs, which are carefully attached underneath their bodies. These crabs are highly attractive to Aldabra rails and other birds eyeing up the energy-rich eggs and it is quite common to see an egg-bearing coconut crab trying to evade a very interested rail while on her way down to the sea to release her eggs! Other than this, these crabs have few predators on the atoll and are fairly abundant on Aldabra. Aldabra’s coconut crab population is healthy thanks to its protection but in other unprotected areas coconut crab populations have disappeared or been substantially reduced by human consumption.

Sometimes referred to as the ‘black and white suited gentleman’, these elegant and beautiful waders are seasonal visitors to Aldabra and at times can be seen in large flocks. Aldabra is home to 4–6% of the global population of crab plovers (Dromas ardeola) when they overwinter on the atoll (Pistorius & Taylor, 2008). Although they overwinter on Aldabra and spend most of the year there and across the Indian Ocean, crab plovers leave the atoll from April to July for the Persian Gulf where they breed. Crab plovers are unusual in being the only wading bird that nests in burrows in sandy banks. An unmistakeable bird, their long legs, upright posture and heavy bill separate them from other wading birds. Indeed their bill is unique among waders and, as its name suggests, is the perfect tool for eating crabs. These unusual characteristics have led to it being classified as the only species in its genus (Dromadidae). This means that crab plovers have no close living relatives in evolutionary terms. On Aldabra these birds have been monitored daily on Settlement Beach at Picard Island for over a decade, to assess their abundance within seasons and between years.

Endemic to Aldabra, the striking black Aldabra drongo (Dicrurus aldabranus) with its red eyes and distinctive forked tail, is one of only two endemic bird species (as opposed to sub-species) of the atoll. The drongo is found on all four islands of the atoll and is relatively common. The drongo carefully constructs neat, cup-shaped nests from casuarina needles, grass and spider webs usually in the fork of a horizontal tree branch. The drongo parents are extremely aggressive around their nests, chasing off any intruder that dares to come near. Drongos usually lay 2-3 eggs at the beginning of the northwest monsoon and fledglings remain with their parents for several months. The persistent call and grey appearance of the fledgling drongos makes them easily distinguishable from their parents and other birds. This charismatic bird can be seen in all types of habitat in the terrestrial environment and feeds on small insects and vertebrates plus birds eggs, and even seabird chicks. It also has cannibalistic tendencies and has been seen on Aldabra consuming its own (previously deceased) young. The Aldabra drongo is included in the long-term Aldabra landbird monitoring programme and data suggests that the population is currently stable (van de Crommenacker et al. 2016).

Gallery

Threats

Several invasive alien species have been introduced to Aldabra since it was first visited by humans. These species either prey on or compete with native species, with untold effects on the biodiversity of Aldabra. Examples include feral goats (eradicated in 2012), black rats, feral cats, Madagascar fodies (eradicated in 2017) and several invasive plants. SIF is taking measures to research, remove or control these species and has a biosecurity plan in place to prevent further introductions.See EU project page for further info.

Rising sea levels, changes in weather patterns and increasing sea temperature all have serious implications for the health of the Aldabra marine and terrestrial environments. As a low-lying atoll, sea level rise will considerably alter the shape of the atoll and reduce the terrestrial area available for its endemic species. Sea level rise and warming are also likely to have severe impacts on Aldabra’s marine ecosystem, in particular the coral reef. A long-term decline in rainfall is already evident and the resulting longer dry periods are likely to affect a number of plant species and the species that depend on them for food or shelter.

The financial costs of operating a research station on an atoll as remote and difficult to access as Aldabra are enormous.The management twinning arrangement with the Vallée de Mai has enabled the entrance fees from this site to support Aldabra, but this mechanism depends on continued tourism to the Vallée de Mai. The lack of long-term financial security remains a threat to the protection and management of Aldabra and SIF is continually looking for solutions to this problem.

The extent of the piracy activities in the Western Indian Ocean dramatically reduced ocean tourism in the outer islands of Seychelles for several years. Up to 2010, Aldabra hosted several cruise ships and dive vessel trips a year which provided much-needed financial support for running the research station. Following this, the worsening piracy situation put an end to nearly all these tourism visits to Aldabra for five years, highlighting the vulnerability of tourism-dependent income. Fortunately, tourism to Aldabra is gradually on the rise again as the immediate piracy threats have lessened with better vessel security and enforcement in the region, but this episode is a harsh illustration of the fragility of tourism as a source of support.

Aldabra is situated close to one of the busiest shipping routes in the Indian Ocean. The International Maritime Organisation has listed the atoll as an area to be avoided by all ships since it is exceptionally important to avoid casualties. There is still a real possibility that if an oil tanker sustained any damage in this area, the subsequent oil spill could have devastating consequences for Aldabra’s wildlife. The recent enlargement of Aldabra’s marine protected area should reduce the chances of such an accident happening in the vicinity of the atoll.

Conservation & Research

Sustainability

Energy

Water

Waste

Aldabra is a site of global scientific interest but its remote location makes operational management a major logistical challenge. In the past the use of diesel generators for electricity resulted in high fuel and transport costs, and was environmentally unsustainable. In 2008, SIF started to investigate ways to increase energy efficiency, and develop a renewable energy system; aiming both to reduce operational costs and their environmental impact. Following an audit of energy usage on Aldabra, renewable energy options and their applicability were assessed, alongside research into energy efficient measures. Reductions in the energy demand were essential for the successful implementation of a renewable energy system. The findings of this research were implemented when a 25 kWp hybrid photovoltaic-diesel energy system was installed in 2012.

In the first year of operation, 94% (38,171 kWh) of the station’s electricity demand was generated by the new solar power system. This contributed to a significant reduction in CO2 emissions (a total of 97,523 kg of CO2 per year were avoided, of which 59% resulted from investments into energy efficiency measures and 41% was contributed by the PV system) and subsequently the research station’s carbon footprint was largely reduced. It is interesting to note that the energy efficiency measures that were undertaken significantly reduced the electricity needs of the station. After reliance on a fossil fuel based energy system for many years this project has revolutionised the operation and sustainability of the research station on Aldabra. Since implementation of the photovoltaic system, diesel demand has decreased by 97% which will lead to a projected saving of €68,000, resulting in a system payback time of only three years. This project has shown that investments into both energy efficiency and renewable energies are essential for an environmentally and financially sustainable system. The reductions in costs and logistical preparation brought about by this project will ensure that SIF can achieve its management and research objectives for many years to come.

Water is a scarce commodity on Aldabra, particularly throughout the long dry season. The fresh water supply for the research station is reliant on rainwater harvesting, with a desalination plant as a backup system. In order to conserve this precious fresh water supply Aldabra uses a dual water system. Fresh water is used for cooking, washing and drinking but salt water is used for the sanitation system. To improve the sustainability of the water management system steps have been taken to employ further water saving measures and maximise rainwater harvesting facilities to ensure a safe fresh water supply throughout the dry season.

With an increasing global population the amount of solid waste being produced worldwide is rising every year. Managing and reducing this waste is a major challenge everywhere, including Aldabra. Operating even a small research station results in the accumulation of household waste. To ensure that this waste is reduced it is all collected, sorted and returned to Mahé where some items are recycled. In addition efforts are made to collect marine debris that is washed onto the beaches of the atoll. Debris is frequently collected from the Settlement Beach on Picard Island, however, collecting marine debris from the more remote places on Aldabra is logistically and financially challenging

To improve the management of biological waste a compost tumbler has been purchased. All of the suitable biological waste produced from the kitchen will now be disposed of inside the tumbler and should produce rich and fertile compost. This will then be used to enrich the soil of the small vegetable garden at the research station. Please check our Sustainability policy for further resources and information about our sustainable practices at SIF.

Visitor Info

Aldabra is a remote and fragile atoll and there are significant logistical challenges in getting there. Designated as a Special Reserve under Seychelles law, SIF operates a limited and strictly controlled tourism policy which supports our objective of protecting the atoll and its biodiversity. All visitors to the atoll must receive prior authorisation from SIF. Please see details in ‘Permissions’ section. Access is limited to specific areas of Aldabra and all visitors must be accompanied by an SIF staff member at all times. Visitors must also abide by SIF’s Aldabra Atoll Regulations.

Accommodation

SIF does not provide accommodation for visitors so you will need to arrange ship-based accommodation onboard the vessel that collects you from Assumption or transports you from Mahé.

Getting there

For anyone wishing to visit Aldabra it is important to realise that the atoll has no airstrip, no harbour or jetty and no helipad. There is no hotel or guesthouse and Aldabra is not set up to accommodate general visitors. All visitors arrive on live-aboard vessels but the activities of such vessels in this region have been severely compromised by piracy in recent years. SIF is not a tourism operator and cannot organise visits, transport or accommodation for tourists. People who would like to visit need to contact one of the operators who include Aldabra on their itinerary. Some of these operators are:

- Silhouette Cruises - www.seychelles-cruises.com

- Masons Travel - www.masonstravel.com

- Creole Travel - www.creoletravelservices.com

- Silversea - www.silversea.com

- Noble Caledonia - www.noble-caledonia.co.uk

- Ponant - us.ponant.com

- SSAB Ltd - https://www.ssabseychelles.com/

The operators will arrange your transport to Aldabra either by plane to Assumption or directly on a vessel.

By Plane

Aldabra is accessible from the main Seychelles Island of Mahé by charter flight to Assumption Island, roughly a 45 km boat ride from Aldabra, and then chartering a boat for transfer to Aldabra (see details below). SIF cannot provide boat connections between Assumption and Aldabra. Flights to Assumption are not scheduled flights and details on chartering a flight must be obtained directly from the Islands Development Company (IDC) who manage Assumption Island and are the sole operator for this route.

By Boat

Visitors can charter a boat from Mahé to Aldabra or arrive on their own vessel. The journey from Mahé usually takes several days. Full details on the commercial vessels that are sailing to Aldabra can be obtained from the Seychelles Tourism Board (STB). Due to the current activities of pirates operating off the East African coast, the Seychelles Ministry of Internal Affairs and Coast Guard have placed strict restrictions on the movements of commercial hire craft operating in the outer islands, so you or your hire company will have to seek permission to provide the required service which includes a security detail. It is recommended that you also seek updated travel advice on the piracy situation from your country’s embassy or High Commission before planning any boat-based travel in Seychelles waters. SIF is not in a position to advise on the piracy situation.

Permission

Any visiting vessel to Aldabra must receive authorisation from SIF before their visit otherwise they will not be permitted to anchor in Aldabra waters or go ashore. Vessel operators/owners may complete a request for clearance form here and submit to SIF for consideration and attach their port clearance documentation.

Fees payable

All visitors are required to pay daily impact fees for visiting Aldabra. The current impact fee is USD 250/day per passenger and crew. The tourism operator will usually arrange for this fee to be paid as part of the package costs but you are advised to check this. For professional photographers and journalists, an additional one-off photography/filming fee will be applied for still photography and video photography, kindly reach out to us for more information on fees.

Frequently asked questions

Aldabra is over 1000km from the island of Mahé in Seychelles. Due to the distance and logistical difficulties in reaching Aldabra it is impossible to visit in one or two days (see ‘Getting there’ section). Depending on your operator, it is advisable that you allow at least several days to visit the atoll to make sure you can appreciate the beauty and uniqueness of Aldabra. However, cruise ship itineraries which include a stop of a few hours are also recommended as many of Aldabra’s highlights can be seen in this shorter time.

There are substantial costs involved in visiting Aldabra, including the cost of transport to the atoll, accommodation on a live-aboard vessel and the impact fee of $250 per person per day to cover the environmental cost of your visit to the atoll. Further details on these are given in the ‘Visitor Info’ section but they will also depend on the operator.

SIF does not organise any trips for tourists to visit Aldabra.If you would like to visit then please see the ‘Visitor Info’ section for more details.

You will need to apply for permission from SIF and the Seychelles Ports Authority before organising a visit to Aldabra Atoll. Please see the ‘Permissions’ section for more details. If you wish to visit any other island in the Aldabra group you will need to contact the Islands Development Company which manages these islands.

SIF does consider visits by professional photographers, filmmakers and artists to Aldabra. You will be expected to cover your transport and accommodation costs (see visitor info section) and there will also be additional photography/filming fees, which will be confirmed on application.

There is a small research and logistics team based at Aldabra all year.Within this team, paid positions are available at times. We also have volunteer positions available as and when needed for certain projects.Please note that there are few international vacancies for paid positions on Aldabra and that competition is very high for both paid and unpaid positions. For these positions we usually seek people with specific advanced technical or scientific skills which are not readily available in Seychelles. Please see our ‘Careers’ section for current available positions.

We are always interested in collaborations with external researchers to further our knowledge of Aldabra and assist in its protection.A research enquiry should be submitted to SIF’s director of research and conservation. Please note that we do not approve all research applications for Aldabra but assess each proposal on: its scientific quality; its complementarity to previous or ongoing research; its likelihood of contributing new knowledge or understanding of Aldabra’s biodiversity, ecology and geology; the logistics of the proposed sample collection; the researchers’ background with the proposed research field; and proposed sampling techniques. Please note that SIF cannot approve proposals to conduct any destructive or invasive sampling on Aldabra. It is sometimes possible and easier for SIF research staff on Aldabra to collect samples for external researchers, particularly for questions addressed at a national, regional or international level (for example much phylogenetic research is done at the regional level and may only require a few samples from a range of locations). In these cases sample collection by SIF staff can save costs and be more efficient than the researcher visiting - this option will also be automatically considered when assessing proposals.

The outstanding universal value of Aldabra Atoll to humanity and the importance of the site in advancing scientific understanding of the natural world are two of the reasons the atoll was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Importantly, the primary activities on the atoll are restricted to scientific research and nature conservation. As such, in the Aldabra management plan, the strategic objective regarding tourism is to “promote and facilitate tourism to Aldabra where activities are closely supervised, do not impact on the site values of Aldabra Atoll and generate financial support for ongoing conservation programmes”.

Aldabra’s value, environmental importance and remoteness are the main reasons people wish to visit the atoll, but the remoteness and difficulty of access pose permanent financial and logistical challenges for managers, researchers and visitors. As such, Aldabra’s general management and research costs are extremely high and are only partially covered by tourism revenue to the site (and only in some years).

A visit to Aldabra, as an exceptionally exclusive destination, is a once in a lifetime opportunity. Opportunities are limited to an average of 445 tourists a year (only 41 in 2010). The impact fee, of €200/day, is an essential contribution to overall management costs and one way that much-needed financial support is generated. The funds raised go entirely towards operations and management of the atoll, and ongoing conservation and monitoring programmes.